|

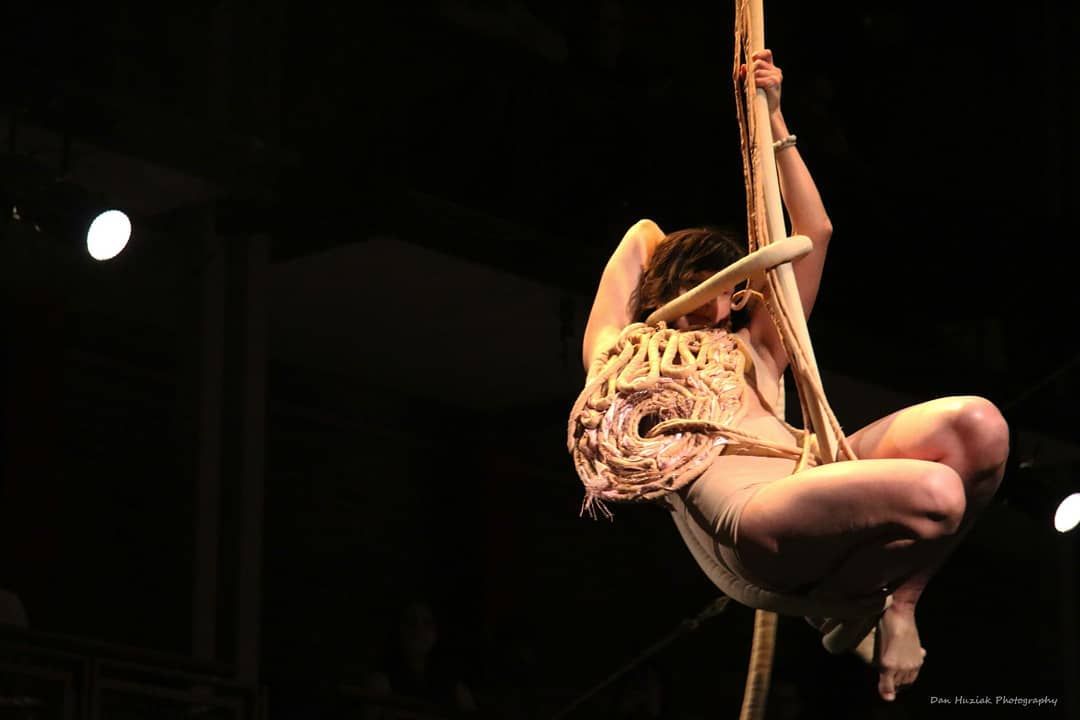

When I was in undergrad, there was a brief period of time where I made art like this: In my first few years of art school, which coincided with my diagnosis and surgery for Crohn’s, I was deeply hooked into the idea of visibility, and invisibility... of my illness and the relational situations I found myself in. Crucial aspects of my identity were in a dance of hiding, revealing, “lying”, strategically informing, and crying for help and sympathy, much needed to beat the isolation of chronic illness. I toyed with different types of prosthetics, inspired by artists like Lisa Bufano who used their visible disabilities so honestly and poetically. I entertained distortion as a lens, to show the ways it shaped a world-view, creating sculptural screens. I shot videos of mundane life stripped of color, manually bending images in space to make the viewer aware of the physicality of perceived distortion. The segway into the work I make today that both extends and subverts these expectations was a sculptural costume, nearly a wedding dress, cut from hundreds of circles of wax paper, stitched into beautiful scars with a resonant sound. This was my first step into dance and improv (a great sculpture and a naive performance) but it was an important marker, and one that nationally forced me into the “visible” category by way of a highly public show at the Smithsonian, through VSA Arts. At the time that I received this attention, I was not emotionally equipped for that kind of direct discussion of my illness. Quite frankly, I used art to talk about it without “talking” about it!! But so it was, this discussion was now a life-path. There are many tricky things about invisible illness beyond just the physical, including nuanced psychological and emotional dynamics. To ground a recent example that highlighted this visible/ invisible barrier: I’ve begun wearing a respirator mask at my job to protect from environmental contaminants. No one else in my facility wears such protection, but I spent the first 3 weeks getting ill at work and freaking out about whether I could keep this job. As a highly-educated female walking into higher levels of production at a textile factory in the ‘hood in Philadelphia, I had both subtle and direct resistances to me coming on board. As soon as I started wearing the respirator, I watched these expressions and interactions soften. I will not try to quantify the psychology behind it, but it was noticeable. This is a “positive” response in many ways, though I have experienced the opposite--direct rage and indignation from superiors who refuse to provide accommodations because they don’t “see” what I’m talking about when I say that I’m sick. I would invite them to observe my bowel movements, but then I think this would piss them off further. These situations have led to direct job loss, panic attacks, many sleepless nights, and any number of head-problems I’ve had to sort out with professional help. There are echos of these reactions in personal relationships as well, and it can be quite jarring to receive rage as a reaction to vulnerability, particularly in one’s inner circle. Sometimes these situations can be healed, other times not. Something I will always grapple with is dignity and right to privacy when it comes to the very personal nature of illness and suffering. It’s a double-edged sword either way you pull it. Withholding information perpetuates isolation, while sharing it can traumatize the listener, revealing embarrassing, grotesque, or incredibly heavy details that neither may have been in the “right place” to digest at the time. These kinds of “reveals” can be quick ways to determine the strength of friendships you might have, but also may cut short the possibility of transmitting something important that both sides might be better off for facing. So in my life--and you can assume this for all other humans--I believe that each person has a right to their privacy and dignity, to choose NOT to discuss anything at all... BUT THEN... ADVOCACY!?! How do we make the world a better, more informed and compassionate place that can include people of all different types of trauma and ability, when we can’t talk openly, for fear of not being able to control our (or their) reactions? What do we share, and how? What if it’s messy? What if they judge? What if I judge? What if suddenly it’s all fucked-up and no one knows where to start the conversation anymore? Do we all walk away? There are many things that I have experienced that I will never talk to you about. Never. Some of these things shape the way I interact in the world in significant ways. Still. Never. Sometimes to share is re-traumatizing for the victim. Sometimes it’s healing. Often the healing happens behind closed doors, and once healed, it’s better for that door to remain shut. How do we care for and hold space, and continue to seek understanding of the invisible aspects of our experience? I have no simple answers but time, reflection, persistence, and humility. To be honest, the only tangible technique I’ve found personally is to believe in art for this, which extends to my advocacy for social art programs. Among the powers that art has, its techniques are abstraction and translation through a medium, providing an opening for difficult, messy, or not-yet-fully-formed messages to be spoken and received. It allows us to draw, sculpt, morph, and phoenix-style rebirth our interpretations as we continue our journey of discovery without judgement, or the perception of judgement, by ourselves or others. If we can come to frame experience without the finality of gains or losses held by momentary reactions, then maybe we can all soften into greater understanding over time. Photo by Chris Robart from "Circus Sessions" produced by Femmes de Feu. Harbourfront Centre Theatre, Toronto, ON

0 Comments

|

Sarah MuehlbauerArtist, writer, seer, circus. Search topics through the Table of Contents to the left, or chronologically through the Archive below.

Archives

January 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed