|

This month I interviewed artist Anne Weshinskey, whose genre-crossing work offers creative resistance to commercial expectation. While her training roots, and foot juggling as an art form, are a product of finely-tuned tradition, her approach to an independent body of work has more to do with contemporary art and concept. Here we talk about “circus” as an expectation, invisible labor, the inevitable state of entropy, and how punk rock attitudes can save US circus.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. Sarah Muehlbauer: So what does your creative practice look like currently? As in, this week? Anne Weshinskey: For the past couple of months, I’ve been focusing on commercial work. It’s something I have to do, create something digestible. Something that looks cool, but has nothing behind it. People only want to see the tricks. Things that look pretty, or nice. I’ve been struggling with that… it’s like it was too easy, and that made it difficult. I kept thinking I’m missing something. I’ve also been fantasizing about making it more practical, something that packs up easily, so that it’s ready to go and I don’t have to think about it anymore. While I’m doing this, I’m also getting other ideas for work I want to make, writing them down, and moving on. Hoping that I’ll remember what I was thinking about when I return to that type of practice. SM: What do you think about these “limitations” that come with commercial work. Do you see commercial work purely “aesthetic”? Is this because we’re not giving audiences credit for being able to digest more challenging or nuanced work? AW: I go back and forth about this. I’m interested in doing more experimentation, guerilla theatre, where you show up with what you have, and don’t say anything about it. This is different from creating an act to get paid for, where there’s an expectation with who’s hiring you. They know what they want. The prospect of money limits you in what you think you can express. That said, even when creating work like this, I have to have a backstory there. I worry a lot about cohesiveness of presentation. People don’t necessarily have the vocabulary of the cultural references I’m pulling from, but I still stick with it because it’s important to me. Ultimately the audience wants to see tricks. The umbrellas are the hardest, most finicky things, they spend so much time to master, but no one cares about that. They only care about me balancing the coat rack, the carpets. It’s like the visual equivalent of muzak. It moves fast (5 minutes is not long), it’s an impressionistic view of things, so much of the thought behind it doesn’t come across. SM: Do you think it’s possible that there’s more that’s interpreted, but just lost in translation? That the viewer is actually receiving more, but their vocabulary to describe art is simply limited? AW: People are finding that lack of meaning, the difficulty of expressing yourself with circus, this limit. It’s always in the back of my mind. The commercial work is a good exercise to contrast with more experimental work. When I’m making commercial work, I feel like I’m not able to step back from the worry about not being able to express myself and go, “does it look cool?”. At the same time, when I’m doing something experimental, I worry that I’m not getting it across. Props and things hinder me from what I’m trying to say or project. I think it’s because of the umbrellas. SM: So what is your relationship to impossible tasks? There is almost a fatalist, or Sisyphean struggle there...an umbrella is always going to be an umbrella. AW: Obviously this is something that’s compelling to me in some way, there’s always some sort of unfinished business in every aspect of art. The whole point of making the commercial act is to have a contained unit and not having to think about it anymore… but once it’s made, I keep tweaking, undoing it, changing the costume, so it’s never finished, there’s not just a bag I can grab and go. The props themselves are always in need of repair. For my act I needed a new coat rack made, so I found an awesome woman who has a welding school in Frederick. Now I’m going to be taking a class in Frederick and learning to make it myself. It adds layers of labor onto things. I try to make low effort art, but it doesn’t really work like that. I had an old collaborative partner from Turkey who had this problem too, where any work we make is so labor intensive, we were complaining about it. Obviously we must get something out if it, the process slows us down to the point where we’re able to get to what we’re going for, and labor is part of the investigation. Maybe it’s just our Midwestern protestant upbringing and work ethic. My husband (sculptor Arni Gundmundsson) is the king of low effort art. He can conceptualize something and execute it with almost no work, and always gets to the point. When we work together, collaboration evens it out. We meet in the middle.

SM:

You performed the first iteration of a piece called “Umbrella Trauma”, a piece that features you carrying heavy buckets of rocks to exhaustion, and foot juggling with paint on your feet. Where does this sit in the realm of Sisyphean tasks? The point of that performance is definitely Sisyphean, literally carrying buckets of heavy rocks until I couldn't carry them. It’s about labor, efforting, and over-efforting. It’s not an “act”, but more like task based performance, the kind of thing where every time you do it is an attempt to uncover why you’re doing it. It wasn’t fully realized the first time, so I plan to perform it again. I wanted to see the image of whiteness on the umbrella, with splashes of color, traces of where my feet hit in repetitive motion. Not repetition in a meditative way, repetition in an annoying way. It’s about labor and the amount of time spent in repetitive motion. Like I’ve spent 10 years of practicing something to show nothing. There was pain and suffering put forth to get to that point. SM: So it seems that the metaphor speaks to invisible labor more broadly, as well as entropy and repair, not just in circus, but in life. What are some of the more social issues that you deal with in your work? And where does this sit with some of our models for capital “A” performance art, which there are very few of...people like Marina Abromovic? AW: I deal a lot with volume and excess, which has to do with repair and entropy for me as someone who has to buy these umbrellas. I have to try to learn how to make them. They’re hard to get, I literally have to go to China to get them. I am not rich, like Marina, so I have to think about the fact that I have real things that are dear, irreplaceable. I want to somehow address issues of limited quantity, of objects that are difficult to make, artisanal things. There’s this perception that if you get things made in China, then they’re cheap. There’s some sort of unlimited supply. But in reality, the construction of these umbrellas is a dying art form. There’s like four families that make them and they’re very hard to get. And now with trade wars and tariffs, things change. I’m not going to do an expose about this, but I’m interested in people’s ideas of what Chinese production means. Slave labor factories, but also fine craftsmanship that is worth something. SM: So you pick up these topics out of your natural instincts and process. What do you think people need circus to be in a holistic sense? AW: In the US, it’s a physical display of prowess. It’s expertise that is presented as a show. It’s pretty much the same as sports, but with music, like figure skating or gymnastics. People are waiting for you to do the tricks. SM: And why is that? Is it an issue of producers not taking risks or giving their audiences credit to digest more sophisticated work? Other structural issues? Structural issues. Not putting value on what’s artistic. Lack of educational outreach. Most arts organizations here stop at educating people, but they don’t do that in other places, like Europe. There are problems with the whole structure of our education system. People are not exposed to art that’s not commodified. “Circus” is commodified because it’s entertainment. SM: So what is the opportunity we have here as American artists? AW: Forget about funding for it. It limits what we can do. To do it our own way, we have to jump it on people. SM: Haha, that sounds almost violent, or confrontational. AW: My background was like this, it’s a conscious approach, this guerilla style of performance. My and my friends almost got kicked out of school for it when we were young. It’s disappointing that after so many years, there’s no recognition, you can’t get grants, or real traction. At the same time, it doesn’t make me want to stop doing it. I see this attitude from a lot of “young artists” that they are waiting for the money, but if you do that, you’ll hold your breath forever. Maybe it’s the generation I’m from, times have changed. With social media, etc there’s so much volume of art, but very little is interesting. Perhaps the idea that “good art rises” is not necessarily the case anymore? When I look at art that’s being collected, there’s nothing in it that you can object to. You wouldn’t say, “I’m so offended that someone painted this”. But people object to experimental circus. People get hostile about it. I’m interested in why they’re mad, how could they object to it? SM: I think as artists we take on any kind of negative projection that society doesn’t want to face. We take on the collective shadow. Perhaps we even trigger insecurity in people who don’t feel they understand the work. Does this feel true? I think people go to gallery nights to see something they haven’t seen, but I hardly see this anymore. I think that when people view art that challenges them, if they can’t “understand” it or don’t have the vocabulary to describe it, then they might feel insecure. Artists themselves say there’s nothing to “get”, whatever you get out of it is fine. If you’re looking at a sculpture, you don’t have to “know”. Maybe the viewer who’s looking at it, it resonates or it doesn’t, but people have this idea that they’re supposed to be feeling something with performance. Then there’s this idea that experimental circus is not respecting traditional circus, but I think that’s wrong. All of my friends who are creators of experimental circus consider traditional circus as art. I think we need to give everyone the benefit of the doubt, to make room for all of it. SM: Do you think perhaps that this reflects society’s gap between intellect and intuition, and what we see as more valuable (intellect)? AW: The way that people create art is based on the environment they’re placed in. This is why I’m interested in incubators, catalysts, artistic communities, environments that establish there is not an expectation that your work has to look like mine. Programs that actually teach you to be artists, not to follow along with a school of art. Americans are stubborn, you’d think that would resonate. I have a fondness for naive art and folk art because it’s intuitive. It’s people trying to connect with the greater world, with whatever materials and heart they have, and no one is really telling them there’s a failure of significance. I feel like circus in the US has that potential, but it’s going the wrong way. Since we don’t have money for the arts, or heavily established teaching structures, the art form can go anywhere. Anybody’s individual interpretation should be celebrated. Being experimental is a good position. Instead, people don’t want to fuck shit up. They are worried about the money. In the punk era money was distasteful, and I still like that mentality. Give us money or don’t. Maybe it’s outmoded, but I would like to meet people who are thinking that way. Of course, I was of a different generation, which is one of the reasons I got into it in the first place, it was still a counter-culture thing. SM: With that said, I will leave our readers with “Sparkle Riot 7”, which is a fun, self-contained performance art video, conceived of as part of Landscape X (artistic interventions in the developing exurban landscape by Anne Weshinskey, Heather Teresa Clark, and Arni Gundmundsson). For me, this demonstrates your thoughtful use of site, and work that is playful, irreverent, and deeply committed to the traditions and people that are part of them.

On Anne Weshinskey: With a background in underground performance art, music, and circus, Anne has never been one to observe the limits of genre, and as a result, her activities are hyper-hybridized. From dancing onstage with rock bands, site-specific installations, sculpture, video, and touring as a professional circus performer, Anne choses her medium based on the situation and her surroundings. As co-founder and co-director of the artist initiative, Caravansarai, in Istanbul, Turkey, she instigated and executed cultural projects in collaboration with European and Middle Eastern artists, curated a group exhibition parallel with the Istanbul Biennial (2013), and participates internationally as an artist and organizer. Since returning to the United States, in addition to concentrating on her own artistic development, Anne has also founded and directs a network for avant garde circus (Risk Agitator for Circus Experimentation) and works as a librarian (MLIS, University of Texas) in the Loudoun County, VA public library system.

0 Comments

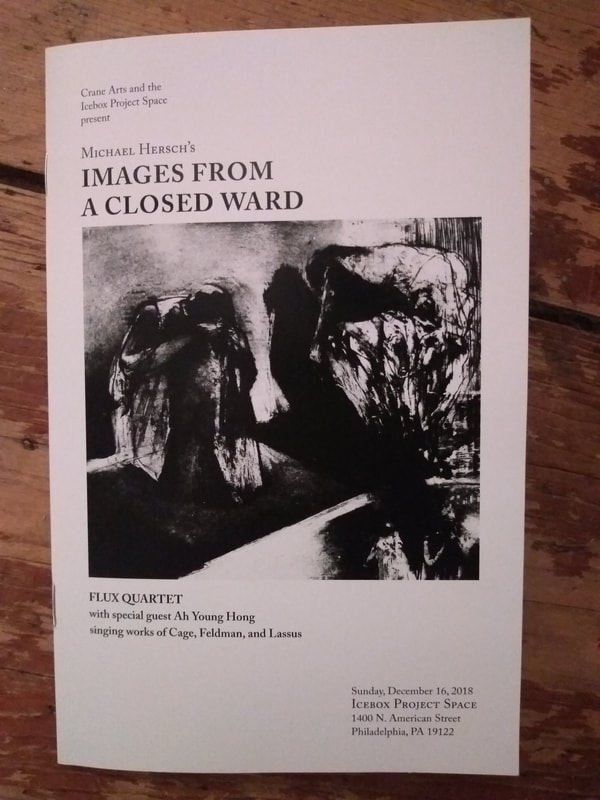

Michael Herch’s “IMAGES FROM A CLOSED WARD” Performed by Flux Quartet with special guest Ah Young Hong singing works of Cage, Feldman, and Lassus. Presented by Crane Arts and the Icebox Project Space. Sunday, December 16, 2018 In the beginning, muddied abstractions of human figures, dark marks create bodies that are alive but not fully human. Etchings and lithographs of Rhode Island psychiatric inmates from the 1960's record a not too distant past, made alive through a quartet's sonic haunting. Strings and vocals narrate images, embodying the “other”. Instruments combine and pull apart with a momentum that plays to our thresholds of adrenaline and empathy. In the images of Mazur's "Closed Ward", bars on windows and stripes on institutional clothes are a reminder of the quest for a sense of order in the individual that is somehow not created by the “outside world”. The atmosphere of the characters is stark isolation littered across crumbling, desolate walls, and even more chilling, in groups occupying disconnected worlds. Repeat phrases like, “This winter all the snowmen turn to stone” pair with rows of bare planks, grave markers for those who died presumably in institution, never finding their way out of a “rehabilitative” environment. At one point, a frame of eyes stares out at the audience, slowly enlarging, and we the viewers become watched, more aware of our spectatorship and implied responsibility. “This winter all the snowmen turn to stone”. Empty beds and rows of toothbrushes become more personal in light of the deceased. Then suddenly we are slammed with intensity, both in sound and in images of brain scans, accompanied by details like age, gender, diagnosis, and death date. This sudden specificity thrusts the viewer into comparison by broad strokes of demographic, and such common, murky categories like “undifferentiated depression”. Now, we are helpless to find lines that bar us from them, or anyone else for that matter. “Canaries beat their bars and scream”. At times white projection space and performers' breath between movements gives space for our hearts to catch up with us. Book-ending vocal works and the only color image used, that of a blossoming flower, provide for the viewer a subtle circular narrative and drop of hope. With it, a sense that while these images and emotions are dire and current, as well as horrific and historic, we can locate our agency in the ability to bear witness to a deep, resonant sadness, and to carry it with us into a brighter future.

Find more about the show at the Icebox Project Space website. written by Sarah Muehlbauer Follow me on Patreon, Vimeo, or sign up for my email list |

Sarah MuehlbauerArtist, writer, seer, circus. Search topics through the Table of Contents to the left, or chronologically through the Archive below.

Archives

January 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed