|

BORDER CROSSING.

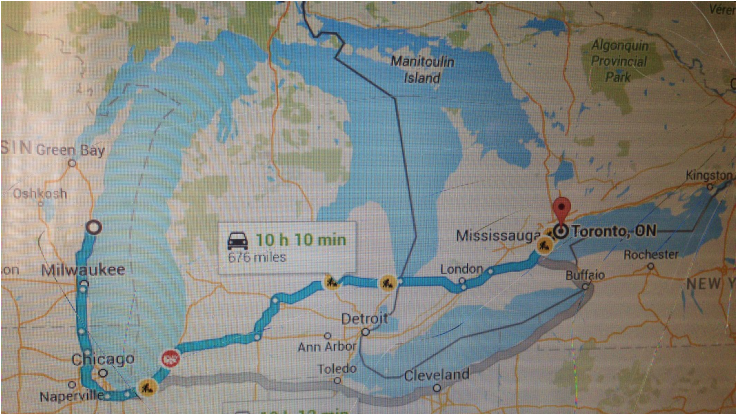

It’s approximately 2:00 pm EST on Sunday January 17th, and I’m approaching the Canada/ US border at Port Huron after my last visit to Xiaolan Health Center, where I am being treated for the management of Crohn’s disease. It’s an epic trek to make regularly, but worth it for the quality of care I receive and the successes that we are slowly carving out. I pull up to the station and hand over my passport. I’ve learned well to have minimal luggage and an orderly car, to answer agents directly and with extra oomph because my voice never seems to project well over the noise. Whenever I’m asked to repeat myself, agents' inexorable suspicion always grows. I am confident that nothing I'm doing is illegal, yet filled with anxiety as I’ve experienced more than once that truth alone is not enough to satisfy agents coming or going from the boundary. Once again my anxieties are about to be fulfilled, and from the moment I am asked to repeat where I live by this gruff, older agent, I can tell that he is seeking to cause a problem. He asks why I’ve come to Canada, to which I respond, “For a doctor’s appointment”—the same answer I’ve given in passage for the last 3 months. I’ve had wildly different handling each time, which reveals to me no “standard” and the sense that my experience is determined by subjective whims of powerful agents. He glares, and the accusation in his voice increases as he demands to know if I am on any medication, for me to hand it over, and to put on my flashers. With anger in his voice and a sincere lack of compassion for my revelation of chronic illness, he demands to know why the pills I have (Prednisone) are in a pill sorter rather than the original prescription bottle. I tell him it’s because I’m traveling and have to take them multiple times a day, and carry them with me in my purse. It wouldn’t make sense to carry containers for the over-the-counter sleep aid I take, as well as Tylenol and Vitamin D, and the steroid that I truly wish I weren’t on, all in separate containers for a weekend of travel. He asks if I’m on anything else, and snatches the tea I have from Xiaolan. I have a sinking feeling that this misunderstanding will only get worse. Clearly my answers don’t satisfy; he leads me to park my car, demanding I leave my phone and purse in it, muttering kids come across the border and sell their friends the “good stuff", clearly indicating that I am being suspected of drug trafficking. Upset, but holding my own, I respond, “Nobody wants to be on Prednisone”, and “If I have to leave my phone in my car, I can’t pull up my prescription information for you,” as I hand over my keys to have my car searched. I enter a cold office full of uniformed agents where I’m escorted to a desk and hand over the orange paper given to me, which is check-marked “fruit and vegetable”. When asked by this next agent about the pill box that is in my hand, I say, “Well I don’t know, but this is the Prednisone I take for Crohn’s disease and is apparently why that agent seemed to be freaking out”. He looked unconcerned about it himself, and with an air of kindness asks me to sit down. Perhaps ten minutes later, another officer travels through the room, catching my gaze and holding up a plastic bag found in my car. And what is this? I give a bit of a laugh and say, “It’s rosin. I’m an aerialist. I use it for performing rope and trapeze. I bought it at a ballet store”. Clearly none of these officers have ever met an aerialist before. I’m informed that they will be testing my tea and the "mystery bag" until they find out “what’s in it”. Since they have no frame of reference for anything I’m telling them, and my own words hold no weight, I know my day has just gotten indefinitely longer. I still have over 300 miles to drive to Chicago to get my friend’s couch, and in the end, I will not make it that far and will end my day in a hotel room in Elkhart, Indiana. I’m escorted to a side room, where I begin the “101 more-and-more personal questions” round of the investigation— which I have been through before on the opposite side of the border-cross. On my first trip to Xiaolan in November I’d been stopped late at night after driving the 450 miles from Wisconsin to the border at Detroit. The longest of the three rounds that instance happened while standing outside in the cold, so I suppose in this case I was thankful to be indoors; though it was quite cold in the office, and after two hours I had a deep chill, and was sick by the end of the day. The interrogation is frustrating. The highly personal and complicated conversation surrounding my health is to be exposed to many unnecessary ears, and has to be projected some distance across a room. I am quizzed by a male agent behind a counter as I'm seated perhaps 20 feet from him, in a room with 4-5 agents coming and going, and one unfortunate young man who’s been snagged for marijuana (he apparently tried to check out the “duty free” shop, without meaning to cross the border at all). The agent asks detailed questions about my treatment, unsatisfied with my answers and the fact that I would drive all this way for an un-finite outcome. Having spent the last 11 years under diagnosis with a disease with no cure, and having to live with this uncertainty and continual questioning and research myself, I am direct with my answers and frustrated with his in-acceptance of these variables. As questioning continues, I describe to him that my illness and the Prednisone I am on affect my ability to handle the stresses that I am now under, and he tells me to “calm down”, which is perhaps the largest insult I received of the day—though to this, I only internally roll my eyes... at the niave insensitivity he must have towards illness in general. In this moment, I conjure an image of his family, his wife and kids, or whomever he may care for, who would not appreciate this attitude, either. I make it through questioning. I sit some more, and eventually lie down across several seats. Some time passes, and a female federal agent who’d been in the room for my questioning comes over and asks me to let them know if I need anything to care for my illness. She also tells me that in the future I can ask to be taken to a separate room, to be spoken to one-on-one, and to request a specific gendered agent if that makes me more comfortable. I thank her. I ask how long I will be there, and no-one can tell me, but it's indicated that a supervisor is involved. More time passes. A few agents exit and re-enter. They are all rubbing their hands, one remarking “this stuff is all over”, and I jokingly ask if they are all covered in rosin now. They laugh, having just passed around a bottle of hand lotion, but appreciating the humor I am finding in my situation. It’s been two hours since I first arrived at border, and yet another officer asks me what I use the rosin for. "I use it to perform trapeze and rope, and for hanging exercises at the gym. You can keep it if you want.” He says, “Yes, we were going to. But we determined that’s what it is. Here you go, I’ll put it in this bag with your other things” (these things being my phone, which they must've taken from my car and searched through, and the teas from Xiaolan, with one open tea bag). I received no apology... but with an air and directness that seems to carry it, I am led out of the security office and given my keys back. I drive on, hitting my physical limit two-hours short of my friend’s house and taking a hotel in Elkhart, IN—another act of surrender that is a commitment to maintaining my health, an oath not to back-slide. As it has been from the start, the journey is challenging—but in a comforting way, though it may seem without a guide, to borrow a line from Paulo Coehlo, the road is “walking me”.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Sarah MuehlbauerArtist, writer, seer, circus. Search topics through the Table of Contents to the left, or chronologically through the Archive below.

Archives

January 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed